You have probably heard the phrase “school of choice” used when describing public education options in Michigan, but what about a “school of no choice?” That was the case for many native Michiganders for over a century.

With November being Native American History Month, Stateside welcomed Eric Hemenway, director of archives and records for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians in and around Harbor Springs, and Sandra Clark, director of the Michigan History Center.

Read highlights below, or listen to the entire conversation above.

On the creation of Indian boarding schools

During the westward expansion of the United States, in which large populations of American Indians were killed, the government decided to establish a number of Indian boarding schools around the country to force the adoption of American culture. More importantly, the schools tried to erase the American Indians’ cultures.

“The idea is to found these Indian boarding schools where Indian children will basically not be allowed to be Indian children anymore,” says Clark.

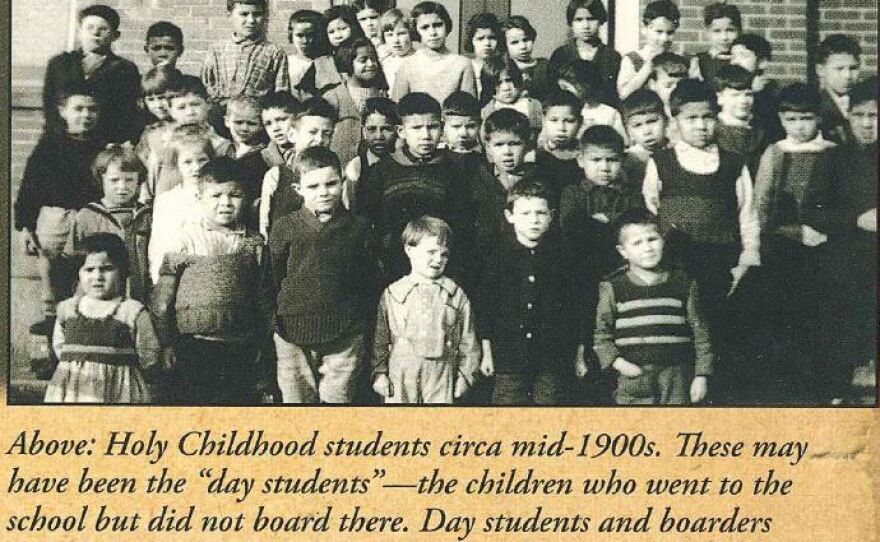

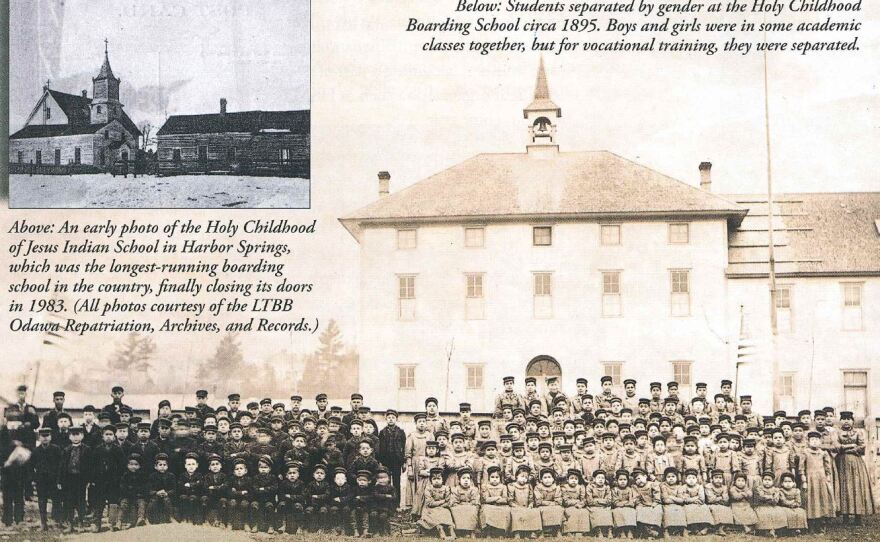

“The boarding schools varied from community to community, but we had one here up in Harbor Springs,” says Hemenway. The school, Holy Childhood, “started out as a mission school that was in conjunction with the tribe and the local Catholic Church. But as federal policies dictated Indian education into the 1880s, the policy said that Indian language was forbidden, Indian dress was forbidden.”

At the boarding schools, Indians were generally taught to be laborers, not any higher professional aspiration like doctors or lawyers, says Hemenway. The students were taught to read and write, but the schools also aimed to “uneducate them on being Odawa.” Students were reprimanded, adds Hemenway, for practicing their culture.

On the schools’ closings

Most of the schools closed in the 1920s, but almost certainly not for moral reasons. The U.S. government didn’t think of the American Indians as much of a threat, and World War I led the U.S. government to reconsider funding the schools because “they were very, very expensive,” says Clark.

“But what makes Holy Childhood an anomaly is that it keeps going for another 60 years,” says Hemenway. “It doesn’t close until 1983 and it’s the last Indian boarding school to do so.”

On impacts on American Indian communities

The large-scale forcing of American Indian children into abusive schools undoubtedly had massive impacts on those communities.

“Loss of language I think is one of the biggest impacts,” says Hemenway. “When these kids were at the school they were forbidden to speak their language, and [there was a] loss of culture, tradition, spiritual beliefs, community ties, family skills.”

Repercussions are still felt today.

Hemenway explains, “We hear devastating stories of kids who survived the school and they grow up to be our elders and, you know, they talk about the situations they went through and how that affected their ability to raise children and develop relationships with other people because of what happened to them at the boarding schools.”

This segment is produced in partnership with the Michigan History Center.

(Subscribe to the Stateside podcast on iTunes, Google Play, or with this RSS link)