The past few years have brought change after change for students in Albion, Michigan.

For years, they saw friends and neighbors hop on buses from other districts every morning. School after school closed and the number of students kept shrinking.

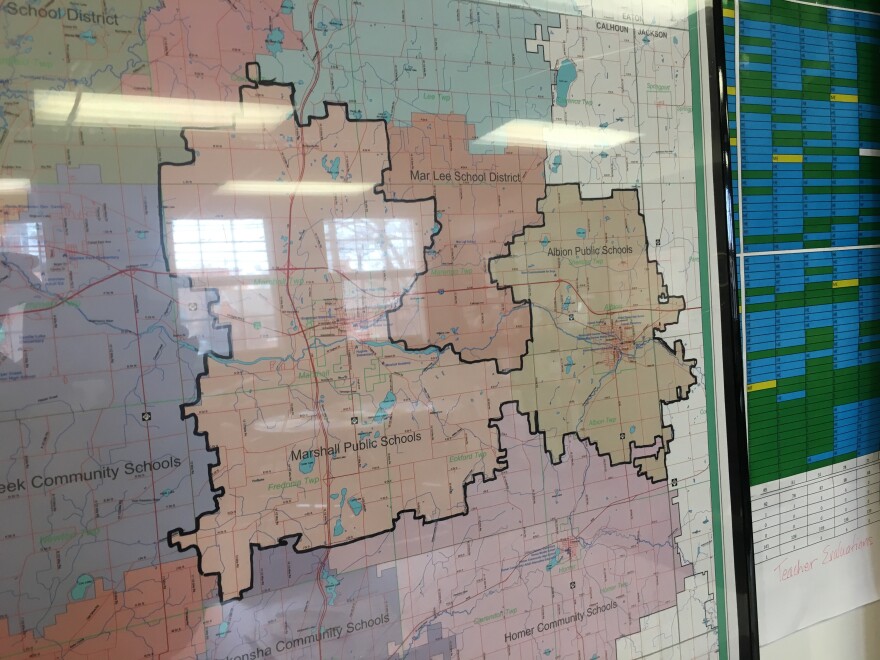

And last year, residents of Albion voted to have Marshall Public Schools take over the district.

That change has affected some Albion families and students in unforeseen ways.

This story is part one of UN/DIVIDED, a three-part series from Michigan Radio

Early morning wake up

Mornings start early at Wanda Kemp’s house.

At 5:30, she is already in the kitchen working on dinner for later tonight. Kemp put her black eyed peas in the crock pot to simmer last night. As she adds the meat to the crock pot, an alarm clock starts going off. It’s coming from the room where Wanda’s two kids are sleeping.

“I think my first one just hit the floor!” Wanda laughs.

Her 8-year-old son Zy’Airh comes out first, and then her 14-year-old daughter Za’Riah. As his sister gets ready for school, Zy’Airh crawls back into bed and turns on the TV. He switches the channel to Nickelodeon. It’s one of his favorite shows: Henry Danger.

“It’s about this little boy being a superhero psychic…” Zy’Airh tells me.

And that is pretty much all I can get out of him. As you might imagine, a show about a kid with psychic superpowers is a lot more interesting than a reporter’s questions -- especially when it’s 6 a.m. and you’re ten years old.

Zy’Airh doesn’t have to be at school for almost three hours. He isn’t really a morning person, but he gets up early every day so he can ride with his sister to her bus stop.

The streets lights are still on when Wanda pulls her black SUV out of the garage. The kids are quiet and sleepy in the backseat. Zy’Airh is still in plaid pajama pants.

Wanda drives a couple minutes down the road. She pulls up to the bus stop and puts the car in park. It’s a few minutes before 6:15 a.m.

Five years ago, Za’Riah could have rolled out of bed and walked to school in less than 10 minutes. You can actually see the old Albion high school from her front yard.

But now, she goes to Marshall High School, a 45-minute bus ride away.

While they wait for the bus to show up, the whole family folds their hands and closes their eyes. Fourteen-year-old Za’Riah starts to pray.

She asks for her mom to be able to get through the work day. She asks God to keep her mind open to learning. And to keep her and her little brother safe.

“God I ask that as we enter the school doors, you’ll open our minds up and you’ll let us be able to go in there and prove to everybody that we are smarter than most people think we are. In the name of Jesus, amen,” she says as her mom chimes in with her own amen.

Two cities, one school district

In Michigan, and across the country, school districts are becoming more segregated – both by race and income.

That makes Albion and Marshall’s story unique.

Students in Albion used to attend an almost entirely low-income, majority African-American district. But last year, Albion residents voted to have Marshall annex – or take over – their schools.

Now, middle and high school students get bussed into Marshall. It’s a mostly white, middle-class city about 13 miles down the highway.

A lot of education researchers will tell you: When kids go to an integrated school, everyone benefits. But parents in Albion were promised they’d still have a school in their city after annexation.

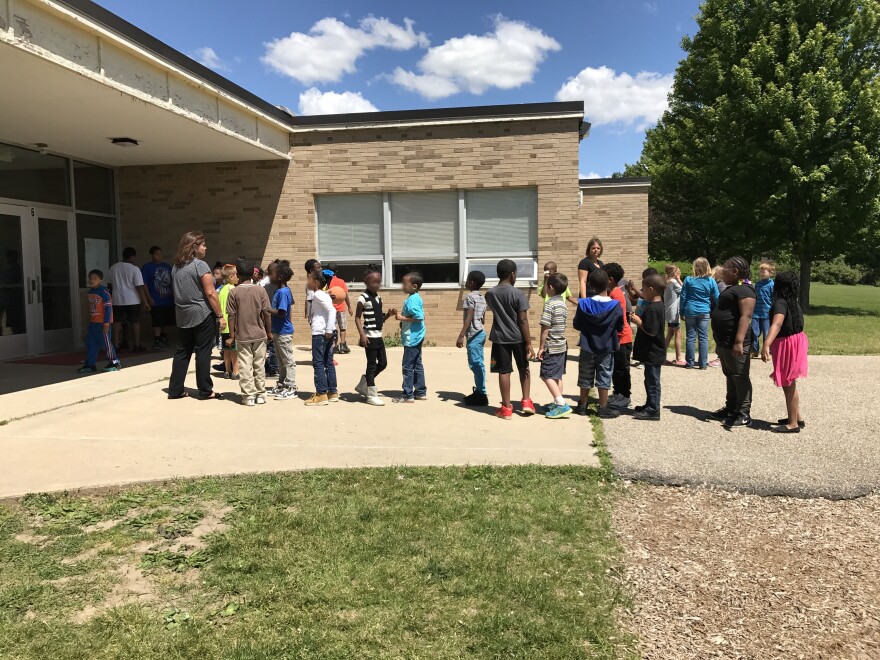

That school is Harrington Elementary, where Zy’Airh is in third grade.

There are no buses that shuttle the district’s youngest students from Marshall to Albion. That means Harrington remains a school with students who are mostly kids of color, and who are almost entirely low-income.

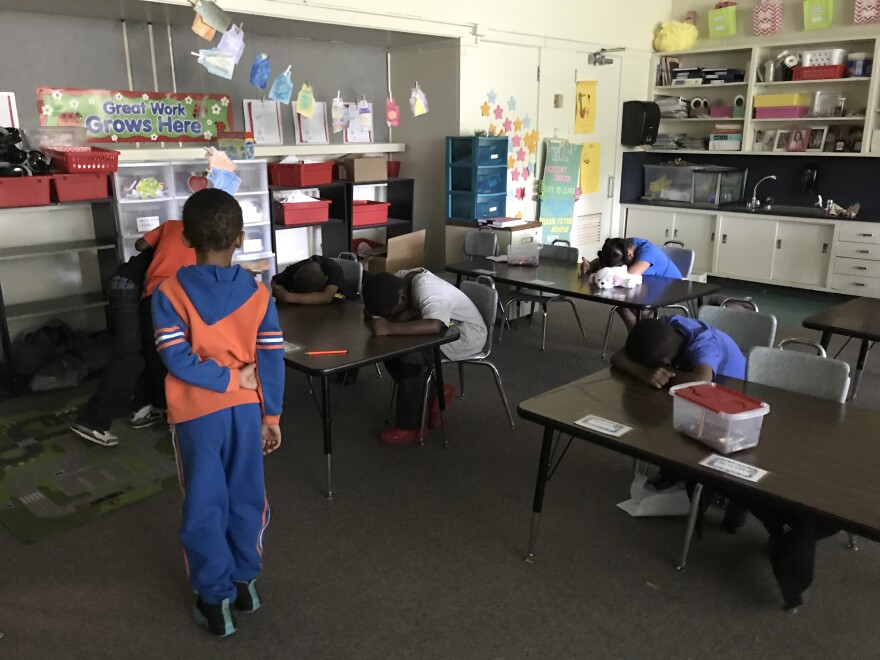

For those students, the first year as part of Marshall Public Schools was not an easy adjustment.

Ups and downs in Harrington's first year with Marshall

The students at Harrington Elementary are happy to tell you what they like about their school. Recess comes up a lot. And so does lunch.

“Hello world, my name is Ty and I am 11 years old…”

For Ty Walker, it’s getting to be a helper.

“I am in fifth grade, and I help little kids like the second graders. That’s why I’m out here right now with second graders. And whatever we do is usually a lot of fun,” he tells me.

Ty says he likes feeling like a role model.

But there is one thing that Ty doesn’t like about his school:

“That people fight,” Ty tells me, punching his fists together.

Ty wasn’t the only student who told me fighting and bullying were problems at Harrington last year. Plenty of parents I talked to felt that way too. But many also had serious concerns about the way the school dealt with students who were acting up, including Zy’Airh’s mom, Wanda Kemp.

“At the age of kindergarten through third grade what is children doing that bad that you're kicking them out of school, that they're being suspended and sent home from school?” Kemp asks.

And there were a lot of students being sent home. Harrington Elementary had a little over 260 students last year. It had more than 160 out-of-school suspensions.

That is a really, really high number. And it is much higher than Marshall’s other three elementary schools.

Wanda’s son Zy’Airh racked up so many suspensions, she started getting letters from the state. They said she could face truancy charges for Zy’Airh’s absences. Kemp called the principal at Harrington.

“And I said, ‘Look, do not send another letter to my house talking about how many days my son has missed out of school. When he's missing days because I'm not sending him, I will accept that. But because you're sending him home do not send me another letter telling me how many days he have missed out of school,” she told me.

At home, Zy’Airh is a smiley and energetic ten-year-old. He likes reading – right now it’s the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series. His favorite food is a McDonald’s cheeseburger and fries.

What Zy’Airh really loves, though, is basketball. He spends recess on the basketball court at school. He plays NBA video games with his four-year-old nephew Zachariah.

But when I ask Zy’Airh what his favorite thing about school was last year, this is how he answers:

“Ummm, really nothing.”

He says getting sent home all the time made him mad.

The uneven burden of school discipline

Zy’Airh, like nearly two-thirds of the kids at his school, is black.

And there are lots of data that show school discipline has a disproportionate impact on kids of color. Black students are nearly four times more likely than white peers to get suspended. They’re twice as likely to be expelled.

Harrington Elementary had a little over 260 students last year. It had more than 160 out-of-school suspensions.

That context wasn’t lost on Wanda Kemp. She remembers reading an Ebony article about the so-called “discipline gap.”

“And they were just saying how the way they suspend the kids K through third I think she had set the set up for failure. You prep our children for a system. I don't want to see my son in the [criminal justice] system when he's older,” says Kemp.

During the 2013 school year, Albion Public Schools suspended 17 kids. That’s across the entire district--kindergarten all the way through 8th grade.

Now, compare that to last year at Harrington, which, again, had 160 out of school suspensions.

So what changed?

Wanda Kemp says it comes down to one thing: relationships.

“Are you taking the time to establish a relationship and get to know a person? Because a person can have a bad day, a bad week, can even have a bad month. But does that mean that’s that person?” she asks.

New district, new problems

Around half of the teachers from Albion were rehired to work at Harrington last fall. Third grade teacher Deb Sealey was one of them. She’s been teaching in Albion for more than 20 years. And she told me when Marshall took over, there were some really big improvements.

In the final year of Albion Public Schools, she had a class of 32 students. She was all on her own in a classroom without any air conditioning. Last year at Harrington, she got part-time support from a classroom aide.

“And I only have 21 students. So this is wonderful,” she said.

But Sealey told me it was still a rough adjustment. They weren’t fully staffed when Harrington opened. Four teachers left after the school year started. The district struggled to find long-term substitutes.

“And I don't think the administration understood how much support we need with our kids that are at risk. And it's been kind of an upstream, uphill battle trying to get things in place,” Sealey said.

Teachers weren’t the only ones who were frustrated with the way things were going. Parents were too.

“This year I feel like has just been changes after changes. And until we have a steady staff that the kids are getting used to, then it’s not gonna get better. We need to have a steady staff on hand here,” said Katie Burton.

Her daughter Layla was just finishing up third grade when we talked at a school picnic last June.

Burton says all the changes in staff created a toxic culture at the school. Bullying was a huge problem for her daughter, she says. When she tried to address it with administration, Burton told me she got a lackluster response.

Burton told me she’s happy Layla can go to her neighborhood school. But she also said things have to be better at Harrington this year.

And Randy Davis says they will be.

“There’s a commitment of moving forward in a new way, with new philosophies, with really great supports,” he says.

Davis is superintendent of Marshall Public Schools. And he says he understands the frustration about the school culture last year.

“If parents were feeling stressed out about it, I say I’m with you. I was stressed out about it,” he says.

Davis also acknowledges there were a “grossly disproportionate” number of suspensions. He says that is not the kind of school he wants Harrington to be.

“Out-of-school suspensions for elementary students don't do an awful lot of good. You know, the idea is how do you keep them in the buildings and teach them how to relate to each other, engage with each other,” Davis says.

Marshall is committed to doing things differently, he tells me.

Which is why in May, with less than a month of school left, Davis fired Harrington’s principal – and brought in Dave Turner to steady the ship.

Turner was the principal at Marshall Middle School.

And more than one person told me he is exactly the kind of person you want in charge of a transition like this one.

Turner told me when he arrived in May, it “was a little crazy.” The systems and procedures that help a school run smoothly weren’t in place. And Turner said it made sense that there were kids at Harrington having a tough time.

“You have some students that have had three teachers this year, while you look at me, here I am 17 days or 14 days so far in this building. And I'm new to them,” he explained.

Those constant changes made it hard for kids to build relationships with the adults in the building. And when kids don’t trust or feel connected to someone, they are more likely to act out. But Turner said it’s not like that is an impossible problem to solve.

“It's not rocket science. We just have to focus on behaviors and relationships and I think we'll be OK,” he said.

Turner didn’t have a lot of time, but he managed to make some real changes.

He rearranged lunch and recess schedules to have more adults on hand. When teachers needed help with a student, Turner was there.

“I told teachers, 'Look here's my number. Text me, call me if you need me,'” he said.

He greeted kids in the morning when they got off the bus and joked around with them. He told corny dad jokes that made them roll their eyes. And he made himself available to parents, too.

After Turner took over, suspensions went way down. In the first 16 days of May, there were 30 out-of-school suspensions. In the last few weeks of school, after Turner took over, there were just five.

A cautious optimism

A lot of parents I talked to felt really encouraged by the way the year ended. But this year, there are more changes in store for Harrington families.

Dave Turner, the one who made all those changes? He is back at the middle school. And Harrington again has a new principal.

His name is Robert Giles, and it’s up to him to convince people the school can turn it around.

“I have to have these babies learn me. Trust me. Have some confidence in me. Love me,” Giles told me a few weeks before the school year started.

Marshall Public Schools has the same challenge Albion did: convince parents to keep their kids in the local school.

So now, Harrington has a new leader. It has a new approach to discipline. And it has more teacher training and family supports.

“And I think their parents, once they see a more inclusive environment, a more cooperative environment, even if they hate the annexation, they’ll see a benefit of what’s going on with their children here,” Giles said.

Ultimately, Marshall Public Schools has the same challenge Albion did: convince parents to keep their kids in the local school. Parents like Katie Burton, who told me if this year isn’t different, she’ll be looking for another district for her daughter.

“I’m gonna give it again a half a year until open enrollment, and if everything’s fine by then, then she’ll stay here,” Burton said.

Marshall needs Burton and parents like her to choose their neighborhood school. Because if it loses too many students, eventually, there might not be a neighborhood school left to choose.

Click here to see Part 2 of UN/DIVIDED, a three-part series from Michigan Radio.